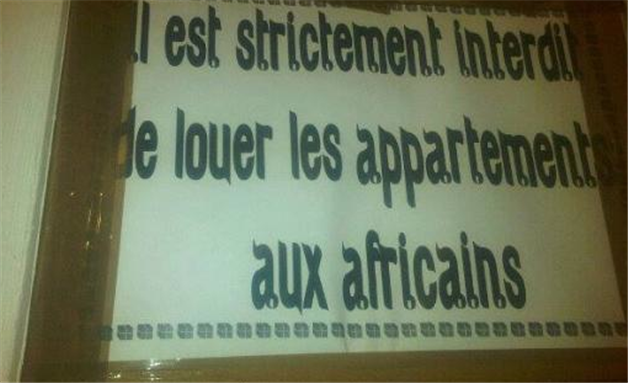

“It is strictly forbidden to rent apartments to Africans,” read a sign in a Casablanca apartment building. France 24’s citizen media section, “Les Observateurs,” initially picked up the story of the signs in the apartment building. They were then later reported on independent Moroccan media. The report accompanying images of the sign gives an account of a student from Cote d’Ivoire who experienced a forced eviction from her apartment building in 2012. Detailing her experience under the pseudonym Nafissa, she describes the process, which neighbors instigated and police carried out: “Our landlord tried to support us but after facing pressure from others, he gave up and asked us to leave, which we refused to do. On 1 January 2013, the police came and asked us to leave. We told them that we know our rights so they did not enter the apartment. We were then taken to the police. A policeman slapped my friend. We still do not know on what legal basis the police acted.”

This incident is just one of many that black African migrants must face in Morocco. And while it was only this past July that members of parliament addressed the urgency of drafting an anti-racism law, the history of racism and treatment towards black Africans stems back centuries ago to the slave trade, which Morocco was heavily involved in. Chouki El Hamel raises points about the history of what he describes as "Black Morocco.” While there are nuances with regard to the treatment black Moroccans versus black non-Moroccan Africans must face, the state`s complicity in perpetuating such deep-seeded racism is important to note. The state`s complicity spans from carrying out racist policies, such as the police forcibly evicting the tenants of an apartment, to racist depictions of black Moroccans and non-Moroccan Africans on state media. There is a perverse logic in the sign mentioned above simply using the term "African" to refer to black non-Moroccan Africans, despite the obvious fact that Moroccans are Africans by virtue of the country`s geographical location. In conversation, many Moroccans refer to Africa and Africans as if they themselves were removed from it, often using Africa and Africans to refer to sub-Saharan Africa and sub-Saharan Africans. Yet, when the prevalence of racism in Morocco is brought up as a point, the dominant narrative argues that it is not "widespread," suggesting, for example, that because segregation is not institutionalized in public spaces, then racism does not exist. This liberal view of racial politics dismisses the placement of privilege and the pervasiveness of embedded misperceptions towards both black Moroccans and black non-Moroccan Africans. Such a view carries dangerous consequences for those who are on the receiving end of this treatment that has gone virtually unaddressed up until recently.

Firstly, it is important to make a distinction between black Moroccans and black Africans migrating from other countries. This distinction is not an attempt to gloss over black Moroccans as a racial group, such as Arab black Moroccans and Amazigh black Moroccans. Establishing this nuance prevents a historical rupture that would otherwise consider black Moroccans as non-indigenous while also factoring in the varying contexts and conditions black African migrants face. A surface and obvious reaction would argue that Moroccans are Africans, and that a nominal categorization that suggests the separation of the two identities is exclusive. However, the racial politics that shape the treatment and perception of black Moroccans and black African migrants carry different factors that should be considered within their own contexts. Such a framework will also reveal that there is an overlap of power relations and narratives. The best indication of that overlap is in Chouki El Hamel’s seminal work, Black Morocco: A History of Slavery, Race, and Islam. El Hamel breaks down dominant perceptions of Morocco’s history of slavery and the attitudes that developed from its involvement in the global slave trade. He explains: “Blacks in Morocco have been marginalized for centuries, with the dominant Moroccan culture defining this marginalized group as ‘Abid (slaves), Haratin (a problematic term that generally meant freed black people or formerly enslaved black persons), Sudan (black Africans), Gnawa (black West Africans), Sahrawa (from the Saharan region), and other terms which make reference to the fact that they were black and/or descendants from slaves.” The revelation of this historical reference will not come as a surprise to speakers of darija, as some of these terms are still used in today’s colloquial dialect to refer to black Moroccans, irrespective of their ethnic origins, and most usually by light-skinned Moroccans.

It becomes evident, then, that a historical presence of a racial hierarchy imposed a certain narrative and influenced etymology. More importantly, this was a process that some version of a centralized authority upheld, whether it was a sultan’s palace or today’s modern state in Morocco. For example, state media has also played a role in its use as a medium for propagating racist views towards black Moroccans. An example is comedienne Hanane Fadili’s sketch imitating a black Marrekchi woman by the name of Lalla Tamou, as a guest on the popular cooking show hosted by Choumicha. The sketch is based off a real episode and became one of her most popular clips, clocking in over six hundred thousand views on Youtube. In her imitation of Lalla Tamou, as a light-skinned Moroccan, Hanane Fadili resorts to the use of blackface in her characterization. The episode was aired on Moroccan state media, a heavily centralized channel that operates within the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Communication. Mustapha El Khalfi, current minister of communication, faced a question pertaining to race and state media in Morocco during a town hall meeting in the Washington, D.C. metro area with the local Moroccan community. During the April 2012 meeting, an attendee asked El Khalfi about the low representation of black Moroccans in state media, whether as hosts, anchors, or actors in movies and sitcoms. He argued there was “no strategy” for deliberately excluding black Moroccans, and that the law “does not forbid” black Moroccans from their involvement in state media. Still, even during the month of Ramadan, the annual height of sitcoms, movies, and other entertainment shows on state media, black Moroccans remain largely unrepresented. El Khalfi’s response was buried in a familiar liberal discourse that disregarded the nature of racial politics and its history in Morocco.

[A clip from Hanane Fadili`s sketch where she used blackface that was aired on Moroccan state media.]

The state’s distribution of power and privilege along racial lines comes into play in more pervasive ways, as is the case with the ongoing territorial dispute over the Western Sahara. The racialization of the Sahrawi population has served the state’s narrative in sustaining its policies towards the territory. As Chouki El Hamel mentioned, the ethnic term “Sahrawi” has historically been used to characterize black Moroccans, regardless of their self-identified ethnicity. This racialization of the Sahrawi population, which carries exclusionary connotations, has had adverse effects on the state narrative toward the Western Sahara as a territory “originally part of Morocco.” The constant distinction of the Sahrawi hassaniya dialect, Sahrawi traditional dress, and Sahrawi traditions, among other distinctions, as inherently Sahrawi has placed the state in a position whereby the cooptation and appropriation of these references has been necessary to hold onto claims of the territory. This cooptation and appropriation is demonstrated through entertainment on state media, the placement of Sahrawis in positions of power as token voices, and even the exotification of Sahrawi women through representations in the media. Yet the racialization of the Sahrawi population has also benefited the state in other ways, allowing it to tout a certain narrative toward the Sahrawi population in support of independence and self-determination, especially when that racialization imposes a hierarchy. In such instances, it becomes easier to dismiss those in favor of independence as an “other,” as the Polisario Front is often characterized in state narratives. The racialization, under these circumstances, involves the resignification of the term Sahrawi to denote both race and ethnicity, instead of just the latter.

Beyond racism and exclusion in state media, the Moroccan state has existed as a protective shield, providing a space for the deplorable treatment and policies towards black African migrants. Such measures are most obvious on the local police level, as was the case in an incident last year that drew widespread attention and outrage. On 29 October 2012, Eric William, a Cameroonian citizen, was arrested in Rabat after attending the trial of Camara Laye, former president and coordinator of the Council of Sub-Saharan Migrants in Morocco. Eric William was given no reason for the cause of his arrest, was thrown into a van with other arrested black African migrants, was beaten and subjected to racist insults, then transported to Oujda, a city on the Moroccan-Algerian border. Upon arrival, after being deprived of food and water, police grouped Eric William and the others who were arrested, led them toward the border where the group was met with warning shots coming from the Algerian border. They then dispersed back toward Oujda, where locals provided them with food and water. The case was detailed in an open letter to the European Union signed by a number of Moroccan civil society groups, human rights organizations, writers, activists, and scholars.

Eric William’s case revealed a disturbing migration policy at the center of the relationship between Morocco and the European Union, where Morocco plays border police for Europe. Morocco’s position in this relationship pays to the tune of tens of millions of euros that are used toward “border control projects” in Morocco. Such projects presumably include the gross mistreatment of black African migrants—a point the United Nations special rapporteur, Juan Mendez, raised: “I urge the authorities to take all necessary measures to prevent further violence and to investigate reports of violence against sub-Saharan migrants.” Earlier this year, March 2013, Doctors Without Borders also produced a damning report entitled “Violence, Vulnerability and Migration: Trapped at the Gates of Europe.” The report stated:

The majority of sub-Saharan migrants in Morocco are forced to live in and the wide-spread institutional and criminal violence that they are exposed to continue to be the main factors influencing medical and psychological needs. [Doctors Without Borders] teams have repeatedly highlighted and denounced this situation, yet violence remains a daily reality for the majority of sub-Saharan migrants in Morocco. In fact, as this report demonstrates, the period since December 2011 has seen a sharp increase in abuse, degrading treatment and violence against sub-Saharan migrants by Moroccan and Spanish security forces.

There have been both numerous and recent accounts of the mistreatment toward black African migrants carried out by Moroccan citizens as well, not just security forces. One anonymous student on a grant to study in Morocco from Guinea recounted his experiences:

Often, when I’m just walking down the street, people will call me a ‘dirty black man’ or call me a slave. Young Moroccans have physically assaulted me on several occasions, for no reason, and passers-by who saw this didn’t lift a finger to help me. All my friends are black and they have all had similar experiences.

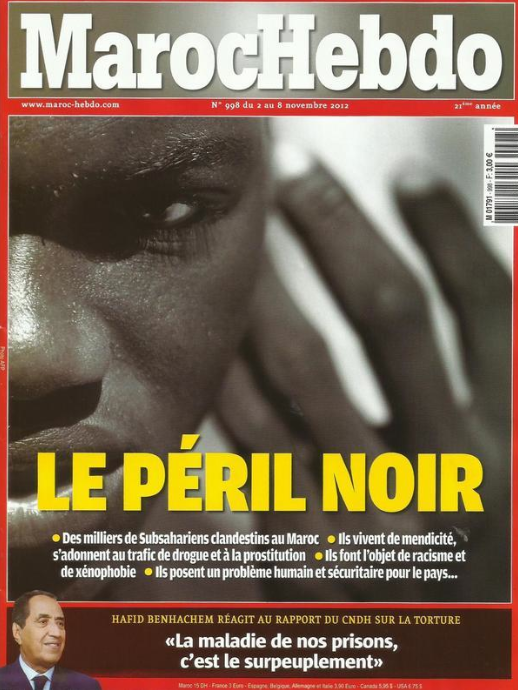

Such treatment is only further enforced through media as well, the worst of which hit newspaper stands only last year under the guise of an “investigative report” published on the weekly, Maroc Hebdo. The cover displayed a zoomed-in image of a black male with the title “The Black Peril.” The magazine faced no legal suit or reaction from the Ministry of Communication over the racist and xenophobic nature of the cover, title, and article.

[Image of the racist Maroc Hebdo cover displaying the image of a black male with the title "The Black Peril."]

Such varying degrees of treatment indicate an embedded racialization that is based on the categorical distinction between black Moroccans and black African migrants. This racialization carries xenophobic elements in which socioeconomics plays a significant role. The widespread perception that black African migrants are involved in drug dealing, human trafficking, and prostitution is tied to the fact that many of the migrants in Morocco are in search of economic opportunity. This pursuit sometimes places Morocco as a transit country, with future intentions of going to Europe. Yet the cyclical racialization places many black African migrants in a trap where sound opportunities become less available due to the perception employers have based on stereotypes on their race, forcing many into unconventional pursuits of income, often times through illegal means.

It was only 15 July 2013 that Moroccan parliament, for the first time, raised the issue of racism on the floor. The royalist Party of Authenticity and Modernity (PAM), a party started by a childhood friend of the king, proposed a measure that would punish “racist acts” with a prison sentence spanning between three months to a year and/or a fine between ten thousand to one hundred thousand dirhams. On the surface, it appears to be a goodwill measure that has drawn support from several human rights organizations. However, the issue of racism toward black Moroccans and black African migrants risks being used as a measure of political opportunism and a smokescreen, a process familiar to the powerful actors of the Moroccan regime. There are certainly no shortages of praised measures that have come out of such windows of political opportunities from Morocco’s parliament; however, they have failed to see the judge’s gavel. The contents of such an “anti-racism” law remain in question, mainly such as how racism will be defined. More importantly, those at the receiving end of the racist treatment are mostly socioeconomically disenfranchised; begging the question of the accessibility of a legal process for those without access to the resources to do so. In an authoritarian context, where the legal system remains heavily centralized instead of independent, and where verdicts are carried out under the name of the king, such a measure is unlikely to yield any change.

![Teaching Palestine Today: On the [F]Utility of International Law](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/63x63xo/bruh250421081905840~.png)